Е. Моралес „Заморац: лек, храна и ритуална животиња у Андима”

Edmundo Morales

The translation was carried out by Alexander Savin, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences.

The original translation is on the page of A. Savin’s personal website at http://polymer.chph.ras.ru/asavin/swinki/msv/msv.htm.

A. Savin kindly allowed us to publish this material on our website. Thank you so much for this invaluable opportunity!

CHAPTER I. From pet to market commodity

In South America, plants such as potatoes and corn and animals such as llamas and kui are widely used as food. According to the Peruvian archaeologist Lumbreras, domestic kui, along with cultivated plants and other domestic animals, have been used in the Andes since about 5000 BC. in the Antiplano area. The wild species of kui lived in this area.

Куи (Guinea pig) this is a misnamed animal as it is not a pig and is not from Guinea. It doesn’t even belong to the rodent family. It is possible that the word Guinea was used instead of the similar word Guiana, the name of the South American country from which kui was exported to Europe. The Europeans may also have thought that the kui were brought from the West African coast of Guinea, as they were brought from South America by ships transporting slaves from Guinea. Another explanation has to do with the fact that kui were sold in England for one guinea (guinea). The guinea is a gold coin minted in England in 1663. Throughout Europe, the kui quickly became a popular pet. Queen Elizabeth I herself had one animal, which contributed to its rapid spread.

There are currently more than 30 million kui in Peru, more than 10 million in Ecuador, 700 in Colombia, and more than 3 million in Bolivia. The average weight of the animal is 750 grams, the average length is 30 cm (dimensions vary from 20 to 40 cm).

Kui does not have a tail. Wool can be soft and coarse, short and long, straight and curly. The most common colors are white, dark brown, gray, and various combinations thereof. Pure black is very rare. The animal is extremely prolific. The female can become pregnant at the age of three months and then every sixty-five to seventy-five days. Although the female has only two nipples, she can easily give birth and feed five or six cubs, due to the high fat content of milk.

Usually there are 2 to 4 pigs in a litter, but it is not uncommon for eight. Kui can live up to nine years, but the average lifespan is three years. Seven females can produce 72 cubs in a year, producing more than thirty-five kilograms of meat. A Peruvian cuy at the age of three months weighs approximately 850 grams. A farmer from one male and ten females in a year can already have 361 animals. Farmers who breed animals for the market sell females after their third litter, as these females become large and weigh more than 1 kilogram 200 grams and are sold at a higher price than males or females who did not have offspring of the same age. After the third litter, breeding females consume a lot of food and their mortality during childbirth is higher.

Kui are very well adapted to temperate zones (tropical highlands and high mountains) in which they are usually bred indoors to protect them from the extremes of the weather. Although they can live at 30°C, their natural environment is where temperatures range from 22°C during the day to 7°C at night. Kui, however, do not tolerate negative and high tropical temperatures and quickly overheat in direct sunlight. They adapt well to different heights. They can be found in places as low as the rainforests of the Amazon Basin, as well as in the cold, barren highlands.

Everywhere in the Andes, almost every family has at least twenty kui. In the Andes, approximately 90% of all animals are bred within the traditional household. The usual place for keeping animals is the kitchen. Some people keep animals in cubbyholes or cages built of adobe, reeds and mud, or small hut-like kitchens without windows. Kui always run around on the floor, especially when they are hungry. Some people believe that they need smoke and therefore keep them in their kitchens on purpose. Their favorite food is alfalfa, but they also eat table scraps such as potato peels, carrots, grass, and grains.

At low altitudes where banana farming occurs, kui feed on mature bananas. Kui begin to feed on their own a few hours after birth. Mother’s milk is only a supplement and not a major part of their diet. Animals get water from succulent feed. Farmers who feed animals only with dry food have a special water supply system for animals.

The people of the Cusco region believe that cuy is the best food. Kui eat in the kitchen, rest in its corners, in clay pots and near the hearth. The number of animals in the kitchen immediately characterizes the economy. A person who does not have kui in the kitchen is a stereotype of the lazy and extremely poor. They say about such people, “I feel very sorry for him, he is so poor that he does not even have one kui.” Most families living high in the mountains live at home with the kui. Kui is an essential component of the household. Its cultivation and consumption as meat influences folklore, ideology, language, and the economy of the family.

Andeans are attached to their animals. They live together in the same house, take care and worry about them. They treat them like pets. Plants, flowers and mountains are often named after them. However, kui, like chickens, rarely have their own names. They are usually identified by their physical characteristics such as color, gender, and size.

Cui breeding is an integral part of Andean culture. The first animals to appear in the house are usually in the form of a gift or as a result of an exchange. People rarely buy them. A woman who is going to visit relatives or children usually takes kui with her as a gift. Kui, received as a gift, immediately becomes part of the existing family. If this first animal is a female and she is more than three months old, then there is a high probability that she is pregnant. If there are no males in the house, then it is rented from a neighbor or relative. The owner of the male has the right to the female from the first litter or to any male. A rented male immediately returns as soon as another male grows up.

Animal care work, like other domestic work, is traditionally done by women and children. All leftovers from food are collected for kui. If a child returns from the field without collecting some firewood and grass for kui along the way, then he is scolded as a lazy person. Cleaning the kitchen and kui cubbyholes is also the work of women and children.

In many communities, baby kui are the property of the children. If animals have the same color and gender, then they are specially marked in order to distinguish their animal. The owner of the animal can dispose of it as he wants. He can trade it, sell it, or slaughter it. Kui acts as petty cash and a reward for children doing chores well. The child decides how best to use his animal. This type of ownership also applies to other small pets.

Traditionally, kui is used as meat only on special occasions or events, and not as a daily or even weekly meal. Only recently have kui been used for exchange. If on these special occasions the family cannot cook kui, then they cook chicken. In this case, the family asks the guests to forgive them and gives excuses for not being able to cook the kui. It should be emphasized that if kui is cooked, family members, especially women and children, are served last. They usually end up chewing on the head and internal organs. The main special role of the kui is to save the face of the family and avoid criticism from the guests.

In the Andes, many sayings are associated with kui that are not related to its traditional role. Kui is often used for comparison. So a woman who has too many children is likened to a kui. If a worker is not wanted to be hired because of his laziness or low skill, then they say about him “that he cannot even be trusted with the care of kui”, implying that he is incapable of performing the simplest task. If a woman or child going to town asks a truck driver or itinerant merchant for a ride, they say, “Please take me, I can at least be of service to give water to your kui.” The word kui is used in many folk songs.

Breeding method changes

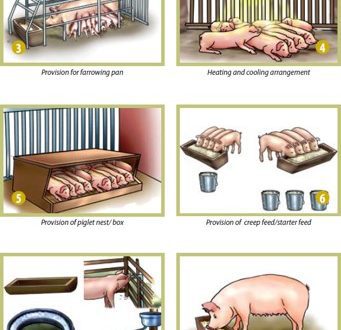

In Ecuador and Peru, there are now three breeding patterns for kui. This is a domestic (traditional) model, a joint (cooperative) model and a commercial (entrepreneurial) model (small, medium and industrial animal breeding).

Although the traditional method of rearing animals in the kitchen has been used for many centuries, other methods have only recently emerged. Until recently, in none of the four Andean countries, the problem of a scientific approach to breeding kui was seriously considered. Bolivia still uses only the traditional model. It will take Bolivia more than one decade to reach the level of the other three countries. Peruvian researchers have made great strides in animal breeding, but in Bolivia they want to develop their own local breed.

In 1967, scientists at the Agrarian University of La Molina (Lima, Peru) realized that animals decrease in size from one generation to the next, as the inhabitants of the mountainous regions sold and consumed the largest animals, and left the small and young for breeding. Scientists have managed to stop this process of crushing kui. They were able to select the best animals for breeding from different areas and, on their basis, create a new breed. By the early seventies received animals weighing as much as 1.7 kilograms.

Today in Peru, university researchers have bred the world’s largest kui breed. Animals that weighed an average of 0.75 kilograms at the beginning of the study now weigh more than 2 kilograms. With a balanced feeding of animals, one family can receive more than 5.5 kilograms of meat per month. The animal is ready for consumption already at the age of 10 weeks. For rapid growth of animals, they need to be fed a balanced diet of grain, soy, corn, alfalfa and one gram of ascorbic acid for every liter of water. Kui eats 12 to 30 grams of feed and increases in weight by 7 to 10 grams per day.

In urban areas, few breed kui in the kitchen. In rural areas, families living in one-room buildings or in areas with low temperatures often share their housing with kui. They do this not only because of the lack of space, but because of the traditions of the older generation. A carpet weaver from the village of Salasaca in the Tungurahua region (Ecuador) has a house with four rooms. The house consists of one bedroom, one kitchen and two rooms with looms. In the kitchen, as well as in the bedroom, there is a wide wooden bed. It can fit six people. The family has approximately 25 animals that live under one of the beds. When kui waste accumulates in a thick wet layer under the bed, the animals are transferred to another bed. Waste from under the bed is taken out into the yard, dried and then used as fertilizer in the garden. Although this method of breeding animals is consecrated by centuries of tradition, but now it is gradually being replaced by new, more rational methods.

The rural cooperative in Tiocajas occupies a two-storey house. The first floor of the house is divided into eight brick boxes with an area of one square meter. They contain about 100 animals. On the second floor lives a family that looks after the property of the cooperative.

Breeding kui with new methods is cost-effective. Prices for agricultural products such as potatoes, corn and wheat are volatile. Kui is the only product that has a stable market price. It is important to note that breeding kui enhances the role of women in the family. The breeding of animals is done by women, and men no longer grumble at women for wasting their time in meaningless meetings. On the contrary, they are proud of it. Some women even claim to have completely changed the traditional husband-wife relationship. One of the women in the cooperative said jokingly that “now I’m the one in the house who wears shoes.”

From pet to market commodity

Kui meat reaches consumers through open fairs, supermarkets and through direct deals with producers. Each city allows farmers from nearby areas to bring animals to sell in open markets. For this purpose, the city authorities allocate special places.

In the market, the price of one animal, depending on its size, is $ 1-3. Peasants (Indians) are actually prohibited from selling animals directly to restaurants. There are many mestizo dealers in the markets, who then sell the animals to restaurants. The reseller has more than 25% profit from each animal. Mestizos always seek to outsmart the peasants, and as a rule they always succeed.

The best organic fertilizer

Kui is not only high-quality meat. Animal waste can be converted into high quality organic fertilizer. Waste is always collected to fertilize fields and orchards. For the production of fertilizer, red earthworms are used.

You can see other illustrations on the page of A.Savin’s personal website at http://polymer.chph.ras.ru/asavin/swinki/msv/msv.htm.

Edmundo Morales

The translation was carried out by Alexander Savin, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences.

The original translation is on the page of A. Savin’s personal website at http://polymer.chph.ras.ru/asavin/swinki/msv/msv.htm.

A. Savin kindly allowed us to publish this material on our website. Thank you so much for this invaluable opportunity!

CHAPTER I. From pet to market commodity

In South America, plants such as potatoes and corn and animals such as llamas and kui are widely used as food. According to the Peruvian archaeologist Lumbreras, domestic kui, along with cultivated plants and other domestic animals, have been used in the Andes since about 5000 BC. in the Antiplano area. The wild species of kui lived in this area.

Куи (Guinea pig) this is a misnamed animal as it is not a pig and is not from Guinea. It doesn’t even belong to the rodent family. It is possible that the word Guinea was used instead of the similar word Guiana, the name of the South American country from which kui was exported to Europe. The Europeans may also have thought that the kui were brought from the West African coast of Guinea, as they were brought from South America by ships transporting slaves from Guinea. Another explanation has to do with the fact that kui were sold in England for one guinea (guinea). The guinea is a gold coin minted in England in 1663. Throughout Europe, the kui quickly became a popular pet. Queen Elizabeth I herself had one animal, which contributed to its rapid spread.

There are currently more than 30 million kui in Peru, more than 10 million in Ecuador, 700 in Colombia, and more than 3 million in Bolivia. The average weight of the animal is 750 grams, the average length is 30 cm (dimensions vary from 20 to 40 cm).

Kui does not have a tail. Wool can be soft and coarse, short and long, straight and curly. The most common colors are white, dark brown, gray, and various combinations thereof. Pure black is very rare. The animal is extremely prolific. The female can become pregnant at the age of three months and then every sixty-five to seventy-five days. Although the female has only two nipples, she can easily give birth and feed five or six cubs, due to the high fat content of milk.

Usually there are 2 to 4 pigs in a litter, but it is not uncommon for eight. Kui can live up to nine years, but the average lifespan is three years. Seven females can produce 72 cubs in a year, producing more than thirty-five kilograms of meat. A Peruvian cuy at the age of three months weighs approximately 850 grams. A farmer from one male and ten females in a year can already have 361 animals. Farmers who breed animals for the market sell females after their third litter, as these females become large and weigh more than 1 kilogram 200 grams and are sold at a higher price than males or females who did not have offspring of the same age. After the third litter, breeding females consume a lot of food and their mortality during childbirth is higher.

Kui are very well adapted to temperate zones (tropical highlands and high mountains) in which they are usually bred indoors to protect them from the extremes of the weather. Although they can live at 30°C, their natural environment is where temperatures range from 22°C during the day to 7°C at night. Kui, however, do not tolerate negative and high tropical temperatures and quickly overheat in direct sunlight. They adapt well to different heights. They can be found in places as low as the rainforests of the Amazon Basin, as well as in the cold, barren highlands.

Everywhere in the Andes, almost every family has at least twenty kui. In the Andes, approximately 90% of all animals are bred within the traditional household. The usual place for keeping animals is the kitchen. Some people keep animals in cubbyholes or cages built of adobe, reeds and mud, or small hut-like kitchens without windows. Kui always run around on the floor, especially when they are hungry. Some people believe that they need smoke and therefore keep them in their kitchens on purpose. Their favorite food is alfalfa, but they also eat table scraps such as potato peels, carrots, grass, and grains.

At low altitudes where banana farming occurs, kui feed on mature bananas. Kui begin to feed on their own a few hours after birth. Mother’s milk is only a supplement and not a major part of their diet. Animals get water from succulent feed. Farmers who feed animals only with dry food have a special water supply system for animals.

The people of the Cusco region believe that cuy is the best food. Kui eat in the kitchen, rest in its corners, in clay pots and near the hearth. The number of animals in the kitchen immediately characterizes the economy. A person who does not have kui in the kitchen is a stereotype of the lazy and extremely poor. They say about such people, “I feel very sorry for him, he is so poor that he does not even have one kui.” Most families living high in the mountains live at home with the kui. Kui is an essential component of the household. Its cultivation and consumption as meat influences folklore, ideology, language, and the economy of the family.

Andeans are attached to their animals. They live together in the same house, take care and worry about them. They treat them like pets. Plants, flowers and mountains are often named after them. However, kui, like chickens, rarely have their own names. They are usually identified by their physical characteristics such as color, gender, and size.

Cui breeding is an integral part of Andean culture. The first animals to appear in the house are usually in the form of a gift or as a result of an exchange. People rarely buy them. A woman who is going to visit relatives or children usually takes kui with her as a gift. Kui, received as a gift, immediately becomes part of the existing family. If this first animal is a female and she is more than three months old, then there is a high probability that she is pregnant. If there are no males in the house, then it is rented from a neighbor or relative. The owner of the male has the right to the female from the first litter or to any male. A rented male immediately returns as soon as another male grows up.

Animal care work, like other domestic work, is traditionally done by women and children. All leftovers from food are collected for kui. If a child returns from the field without collecting some firewood and grass for kui along the way, then he is scolded as a lazy person. Cleaning the kitchen and kui cubbyholes is also the work of women and children.

In many communities, baby kui are the property of the children. If animals have the same color and gender, then they are specially marked in order to distinguish their animal. The owner of the animal can dispose of it as he wants. He can trade it, sell it, or slaughter it. Kui acts as petty cash and a reward for children doing chores well. The child decides how best to use his animal. This type of ownership also applies to other small pets.

Traditionally, kui is used as meat only on special occasions or events, and not as a daily or even weekly meal. Only recently have kui been used for exchange. If on these special occasions the family cannot cook kui, then they cook chicken. In this case, the family asks the guests to forgive them and gives excuses for not being able to cook the kui. It should be emphasized that if kui is cooked, family members, especially women and children, are served last. They usually end up chewing on the head and internal organs. The main special role of the kui is to save the face of the family and avoid criticism from the guests.

In the Andes, many sayings are associated with kui that are not related to its traditional role. Kui is often used for comparison. So a woman who has too many children is likened to a kui. If a worker is not wanted to be hired because of his laziness or low skill, then they say about him “that he cannot even be trusted with the care of kui”, implying that he is incapable of performing the simplest task. If a woman or child going to town asks a truck driver or itinerant merchant for a ride, they say, “Please take me, I can at least be of service to give water to your kui.” The word kui is used in many folk songs.

Breeding method changes

In Ecuador and Peru, there are now three breeding patterns for kui. This is a domestic (traditional) model, a joint (cooperative) model and a commercial (entrepreneurial) model (small, medium and industrial animal breeding).

Although the traditional method of rearing animals in the kitchen has been used for many centuries, other methods have only recently emerged. Until recently, in none of the four Andean countries, the problem of a scientific approach to breeding kui was seriously considered. Bolivia still uses only the traditional model. It will take Bolivia more than one decade to reach the level of the other three countries. Peruvian researchers have made great strides in animal breeding, but in Bolivia they want to develop their own local breed.

In 1967, scientists at the Agrarian University of La Molina (Lima, Peru) realized that animals decrease in size from one generation to the next, as the inhabitants of the mountainous regions sold and consumed the largest animals, and left the small and young for breeding. Scientists have managed to stop this process of crushing kui. They were able to select the best animals for breeding from different areas and, on their basis, create a new breed. By the early seventies received animals weighing as much as 1.7 kilograms.

Today in Peru, university researchers have bred the world’s largest kui breed. Animals that weighed an average of 0.75 kilograms at the beginning of the study now weigh more than 2 kilograms. With a balanced feeding of animals, one family can receive more than 5.5 kilograms of meat per month. The animal is ready for consumption already at the age of 10 weeks. For rapid growth of animals, they need to be fed a balanced diet of grain, soy, corn, alfalfa and one gram of ascorbic acid for every liter of water. Kui eats 12 to 30 grams of feed and increases in weight by 7 to 10 grams per day.

In urban areas, few breed kui in the kitchen. In rural areas, families living in one-room buildings or in areas with low temperatures often share their housing with kui. They do this not only because of the lack of space, but because of the traditions of the older generation. A carpet weaver from the village of Salasaca in the Tungurahua region (Ecuador) has a house with four rooms. The house consists of one bedroom, one kitchen and two rooms with looms. In the kitchen, as well as in the bedroom, there is a wide wooden bed. It can fit six people. The family has approximately 25 animals that live under one of the beds. When kui waste accumulates in a thick wet layer under the bed, the animals are transferred to another bed. Waste from under the bed is taken out into the yard, dried and then used as fertilizer in the garden. Although this method of breeding animals is consecrated by centuries of tradition, but now it is gradually being replaced by new, more rational methods.

The rural cooperative in Tiocajas occupies a two-storey house. The first floor of the house is divided into eight brick boxes with an area of one square meter. They contain about 100 animals. On the second floor lives a family that looks after the property of the cooperative.

Breeding kui with new methods is cost-effective. Prices for agricultural products such as potatoes, corn and wheat are volatile. Kui is the only product that has a stable market price. It is important to note that breeding kui enhances the role of women in the family. The breeding of animals is done by women, and men no longer grumble at women for wasting their time in meaningless meetings. On the contrary, they are proud of it. Some women even claim to have completely changed the traditional husband-wife relationship. One of the women in the cooperative said jokingly that “now I’m the one in the house who wears shoes.”

From pet to market commodity

Kui meat reaches consumers through open fairs, supermarkets and through direct deals with producers. Each city allows farmers from nearby areas to bring animals to sell in open markets. For this purpose, the city authorities allocate special places.

In the market, the price of one animal, depending on its size, is $ 1-3. Peasants (Indians) are actually prohibited from selling animals directly to restaurants. There are many mestizo dealers in the markets, who then sell the animals to restaurants. The reseller has more than 25% profit from each animal. Mestizos always seek to outsmart the peasants, and as a rule they always succeed.

The best organic fertilizer

Kui is not only high-quality meat. Animal waste can be converted into high quality organic fertilizer. Waste is always collected to fertilize fields and orchards. For the production of fertilizer, red earthworms are used.

You can see other illustrations on the page of A.Savin’s personal website at http://polymer.chph.ras.ru/asavin/swinki/msv/msv.htm.